Field Journal

American Goshawk

Seeing an American Goshawk is at the top of any hawk-watcher’s list. But imagine seeing thousands in a season? In 1972, 5,382 goshawks were counted between September and November at Hawk Ridge, the famed hawk-watching site that overlooks Lake Superior on the outskirts of Duluth, Minnesota. The following year, 3,566 were counted. This so-called “irruption,” south out of Canada’s northern forests, was known to occur in roughly 10-year intervals. And so it was that in 1982, Hawk Ridge’s counters saw 5,819 goshawks barrel past their rocky ridge, then nearly 2,000 the following year.

No other single place in North America sees as many goshawks; people come from all over the world to see Hawk Ridge’s numbers, and rightfully so. For as much as any raptor, the goshawk flies on legendary wings. Revered for its strength, a goshawk adorned the helmet of Attila the Hun; its aggressiveness and courage made it the pick of Europe’s medieval falconers.

They’re the biggest and heaviest of the world’s accipiters, the larger cousins to Cooper’s and Sharp-shinned Hawks; fierce stovepipe-shaped hunters with long tails for maneuverability through the forest and short, powerful wings for quick acceleration. As Birds of the World describes them: “They are short duration sit-and-wait predators, perching briefly while searching for prey before changing perches.”

Until recently, Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) was the name of the species, with a circumboreal range from North America across Europe and northern Asia. But studies of genetic and vocal differences recently led to a split into two populations: the American Goshawk (Accipiter atricapillus) of North America, which nests from willow stands along Arctic rivers to montane forests of the desert Southwest, and the Eurasian Goshawk of Europe and Asia. Wherever they’re found, they fiercely defend their nests, notorious, notes Sibley’s Guide to Bird Life and Behavior, “for knocking off loggers’ hard hats and unseating horseback riders.”

What are their unlucky prey? One clue comes from one of their 19th century nicknames, the “partridge hawk.” In the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska, ruffed grouse is the main one, as are snowshoe hares. But more than a century ago, they were heavily persecuted because of that diet, perceived by hunters as a predator of highly valued game species.

What they eat also says something about their migration pattern, and those irruptions which made Hawk Ridge famous. Unlike Broad-winged or Swainson’s Hawks, raptors which almost entirely vacate North America each autumn, adult goshawks tend to stay put when those grouse and hares are abundant, and juveniles will be forced south in search of food. But when populations collapse for those prey, typically once a decade, sizable numbers of mostly adult goshawks empty out of those forests.

As author and naturalist Scott Weidensaul in Living Bird magazine: “Many goshawks that nest across the West appear to be entirely resident, and the same goes for those in the Upper Midwest and East, where the goshawks seen at autumn migration-count sites are usually dispersing juveniles. Populations farther north, especially in the northern Canadian boreal zone from Manitoba to Alberta, also stay put – usually. Sometimes, though, circumstances in the forest take a turn for the worse, and when they do, the result is perhaps the most intriguing facet of this fascinating raptor: a goshawk ‘invasion.’”

When these invasions happen, Weidensaul writes, goshawks extend as far south as Texas and northern Mexico, the Gulf states, and even Bermuda. But are they a thing of the past? The last irruption seen at Hawk Ridge was over 20 years ago; in 2022, only 64 goshawks were counted at the site, the lowest in a quarter-century. The famous eastern hawk-watch site, Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania, saw just one. “Natural cycles of many sorts are slowing or vanishing,” writes Weidensaul.

It’s not only hawk-watch counts, however, that show declines in goshawks. Breeding-bird surveys also support that picture. For decades, scientists have been trying to determine the reasons for that decline, with climate change and clear-cut logging in the likes of the Pacific Northwest and Canada and even West Nile Virus given as potential reasons. Research has shown they need a lot of land for breeding territories, and the timbering of mature and old-growth forests across the West continue to pressure them.

Which is why groups like HawkWatch International and the Center for Biological Diversity have advocated to protect these forests, and petition the federal government to list the American Goshawk as endangered, and in so doing protect mature forests from Alaska to Mexico. With greater protections, these fierce raptors might thrive once again.

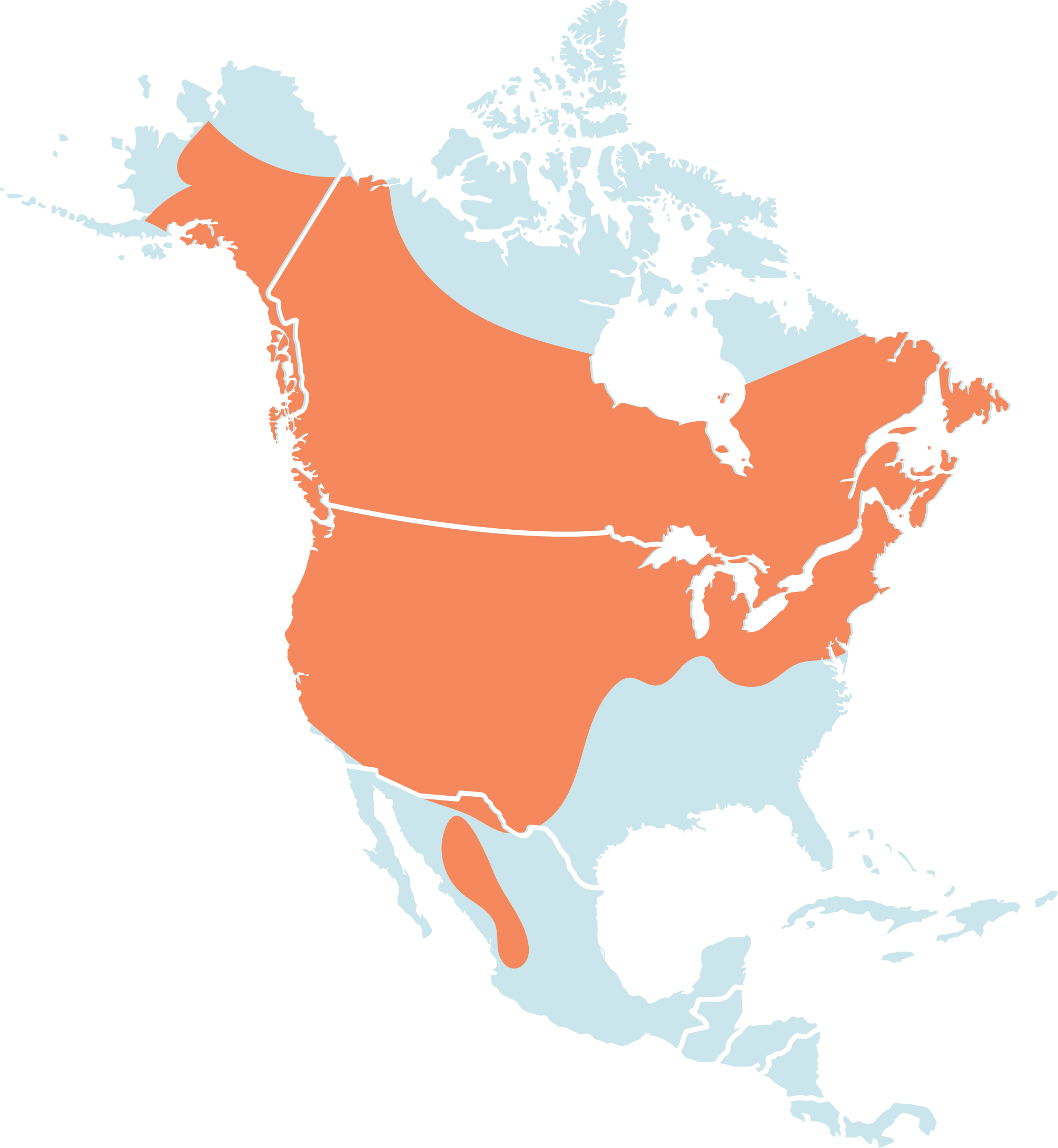

Range

Canada, the northern United States (including much of Alaska), the mountainous western United States, and northwestern Mexico.

Data via eBird Species Maps

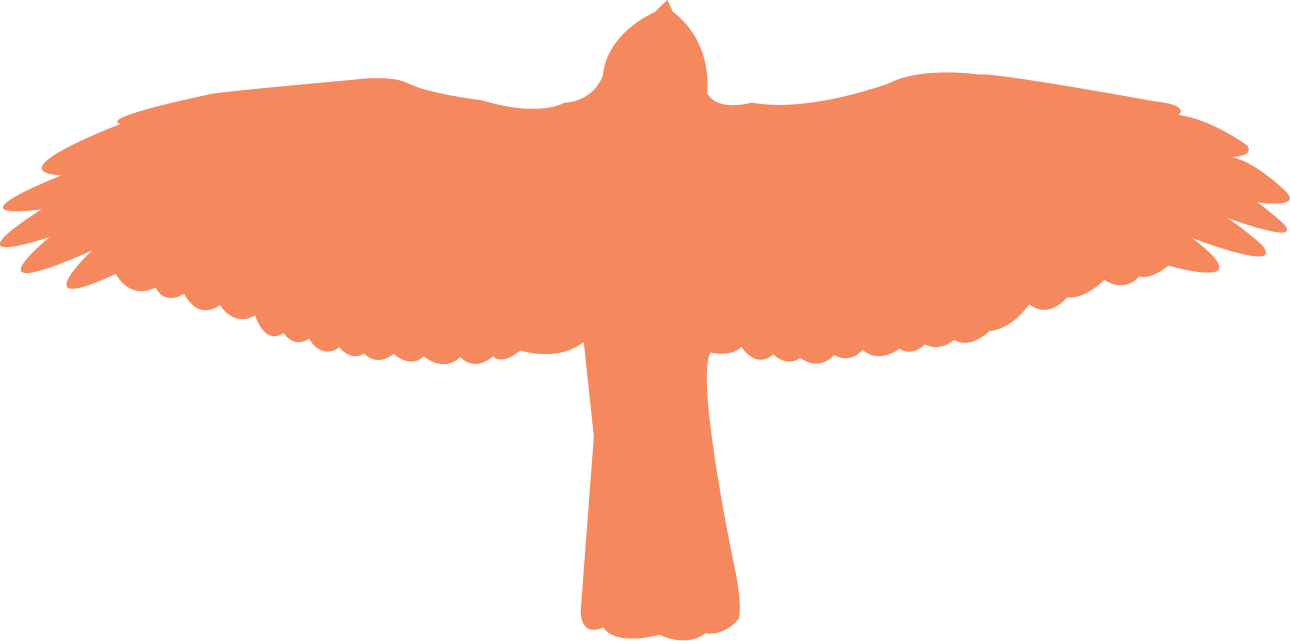

Size and Shape

Length: 20.9-25.2 in

Weight: 22.3-48.1 oz

Wingspan: 40.5-46.1 in

via allaboutbirds.org

Habitat